EXHIBITION 1 -15 FEBRUARY 2026

Janet Graham: The Architecture of Containment

“The Architecture of Containment” was created to confront and dismantle the legacy of Ireland’s Magdalene laundries — institutions built to contain and erase the so-called “fallen women.” In these paintings, I celebrate the demise of that cruel system. As the walls crumble, so too does the structure of oppression that confined generations of women and children.

Each painting explores a different facet of fear, loneliness, and desolation — emotions that defined the lives of those deceived into entering these homes under the guise of care and refuge. The women were promised safety for themselves and their unborn babies, only to find that compassion was replaced by control, and sanctuary by servitude.

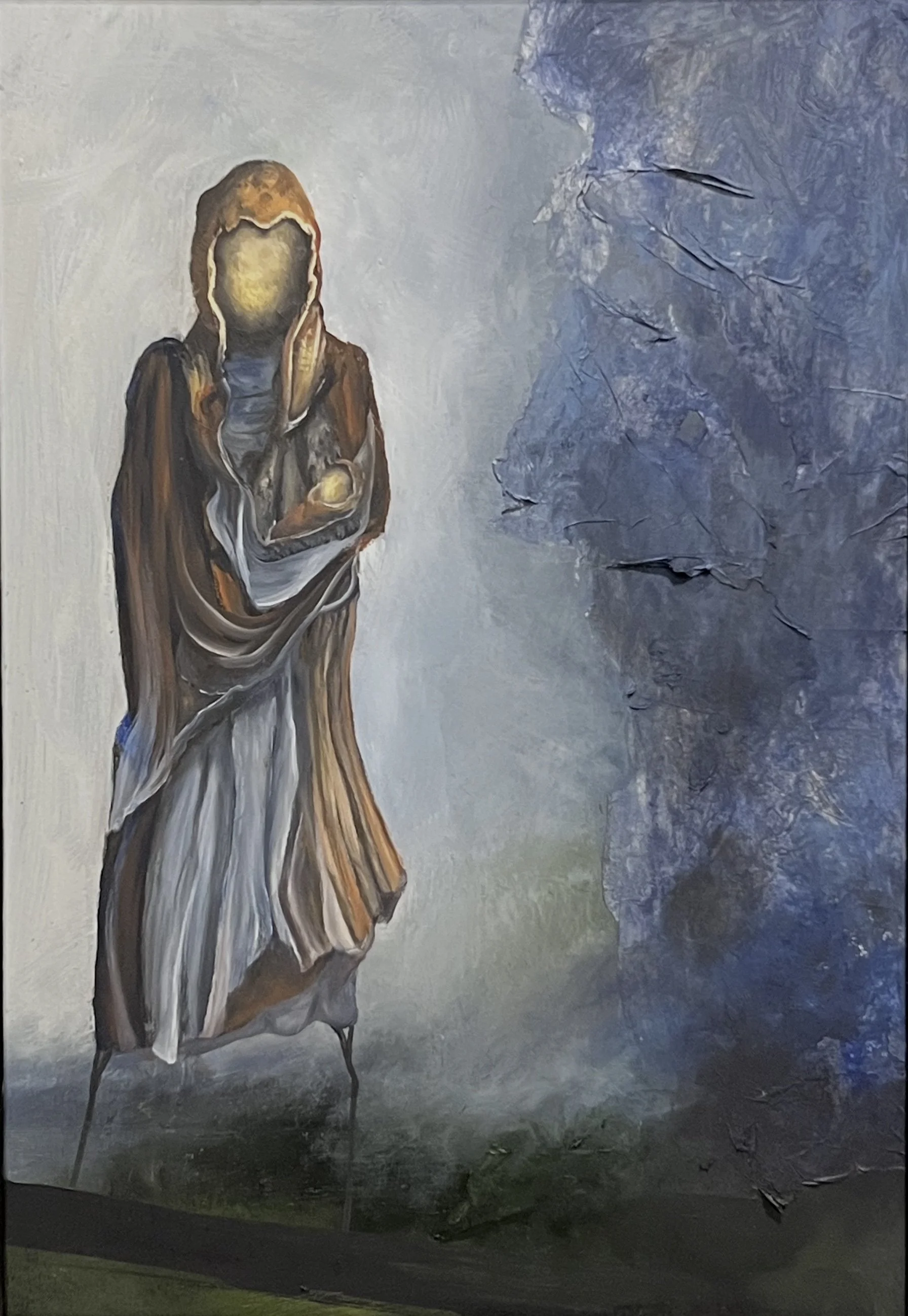

In Crouching, I explore the moment of realization — the instant the pregnant girl understands the truth of her captivity. Her head is bowed in shame, her face featureless. The empty void before her, shaped like a womb, suggests both life and death — a grave and a cradle. At its edge stands the faint outline of a skeletal tree, symbolizing family and endurance, though barely visible, like her fading hope. Stripped of her name and identity, she has become a “Maggie” — the collective term for those imprisoned in the laundries — deemed unclean, unworthy, penitent.

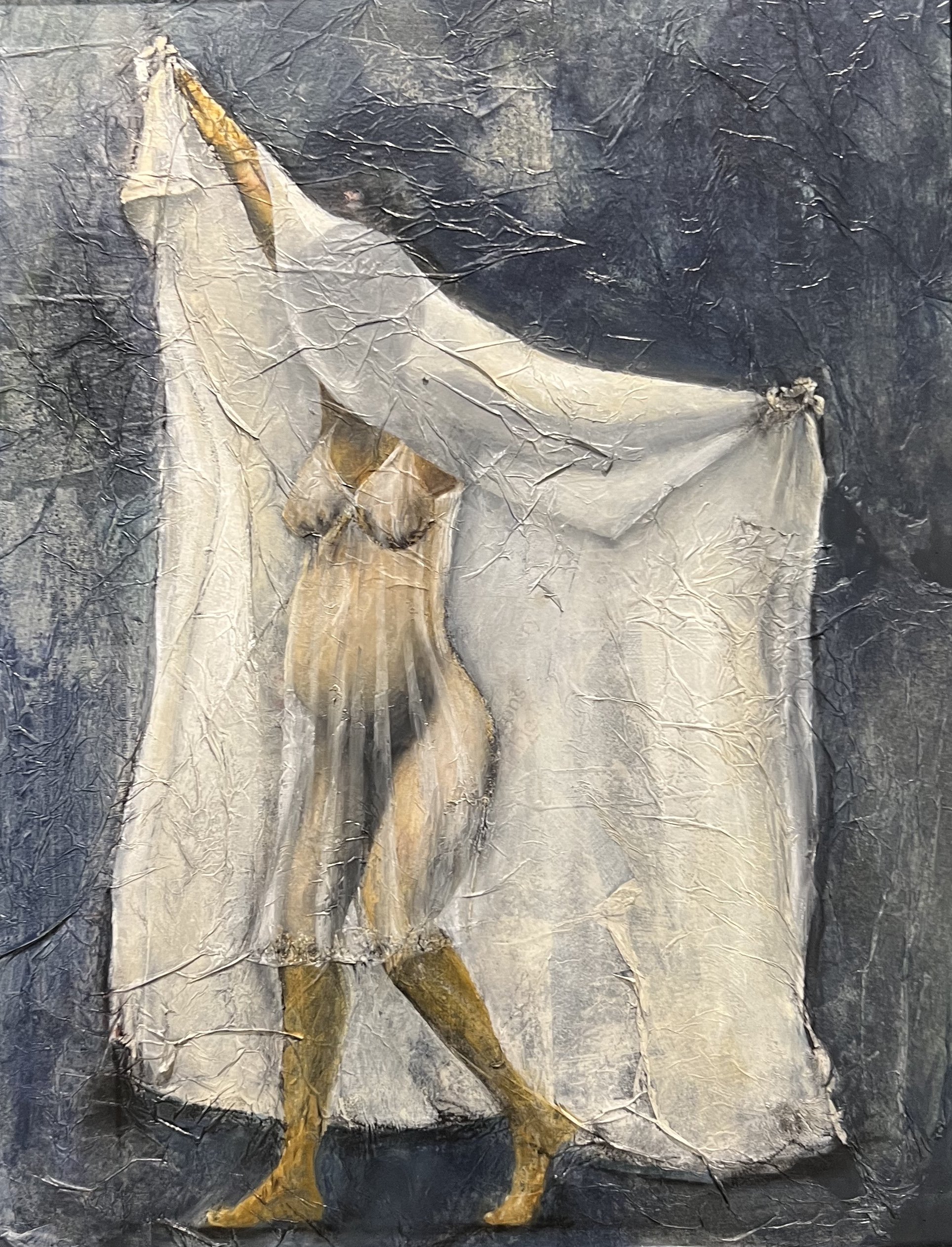

The stance of the figure evokes crucifixion, reflecting the suffering of women newly arrived in the institutions. Their clothes were taken, their hair cut, their voices silenced. In one work, a delicate petticoat dissolves into the cross — the last fragment of femininity consumed by penance. The garments, “hung out to dry,” become symbols of both the laundry labour and the women’s exposure and vulnerability. Diffused sunlight filters through a web of sharp, bare branches, its fractured rays denying even hope. In the distance, the ruin of a church looms — stripped of its power and purpose.

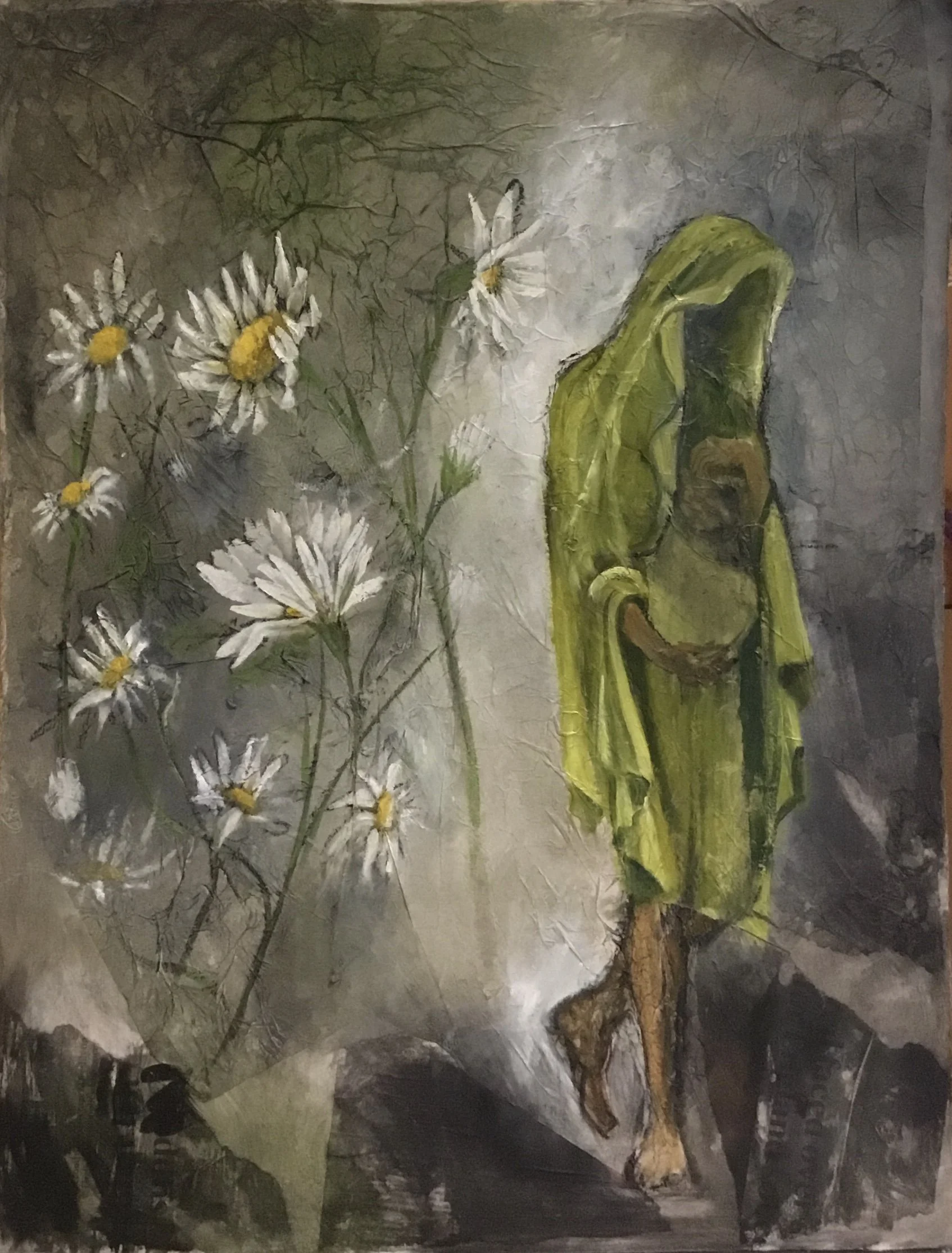

Another painting recalls a tender moment of remembrance. The Lady, Mother, or Tree Nymph watches over a small plot of angels, while soft bog cotton — once used in Ireland for comfort and healing — lies as a soothing shroud for the children buried beneath. The work reflects on the hypocrisy of institutions that claimed to follow Christ, yet violated every principle of compassion, love, and refuge. Beneath the arms of the cross, the shrouds of secrecy disintegrate, allowing truth to rise triumphant. A barn owl — referencing Mary Rafferty’s States of Fear documentary — represents the exposure of hidden truths. Below, iron railings signify the end of incarceration.

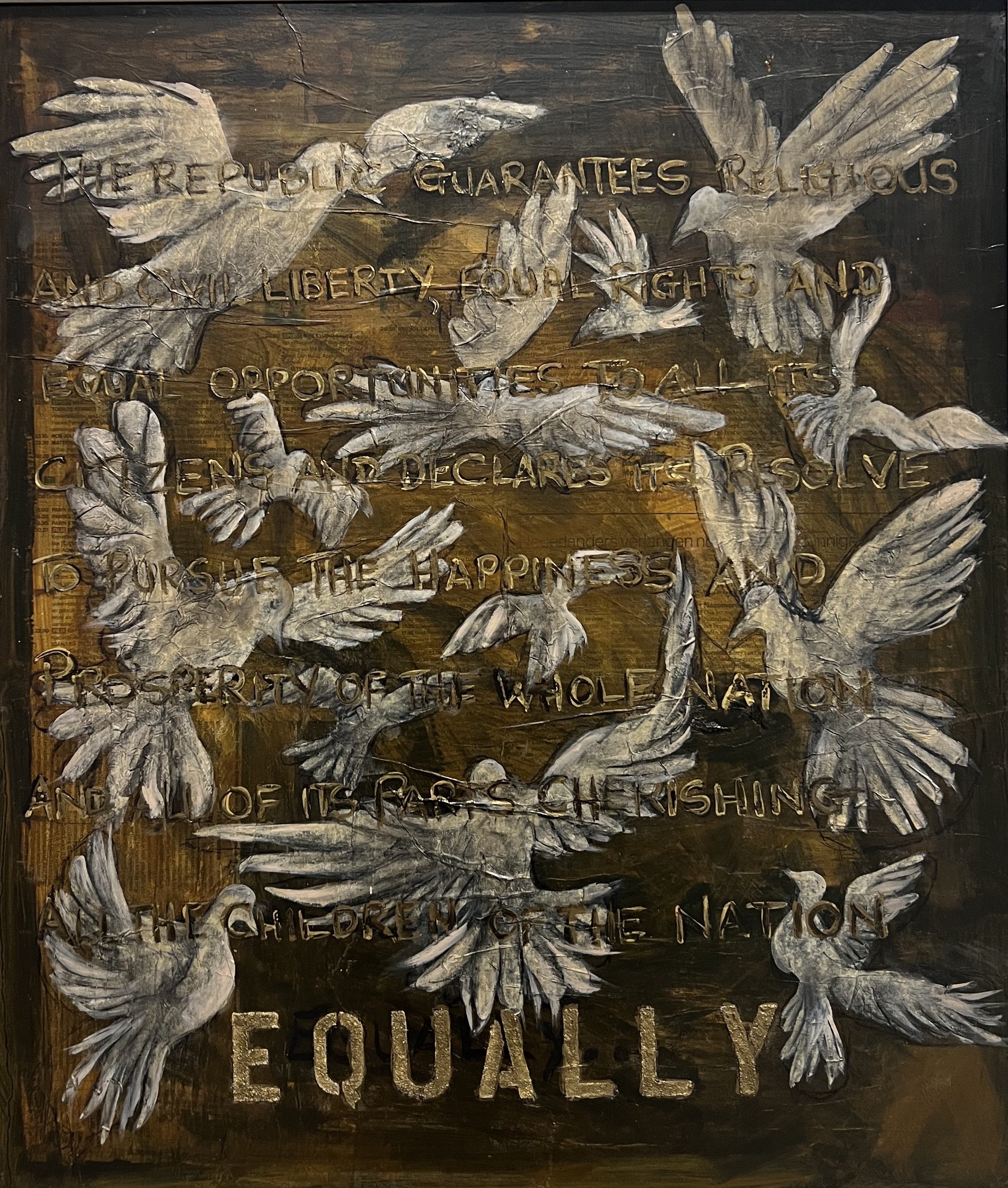

The Mother and Baby Homes were run by religious orders, including the Bon Secours Sisters, whose motto — “Good help to those in need” — now echoes with bitter irony. Beneath one such home in Tuam lie the remains of 798 infants and young children, their bodies discovered in what were once septic tanks. In the background of my work, the outline of the home remains etched like a scar across the landscape. In the foreground, frail women, ravaged by their experiences, huddle together — their solidarity the only light in their collective memory.

Other works in the series trace the lives of these women after release — women who, though freed from physical captivity, remain bound by grief and loss. One figure kneels as if in prayer, naked and humble, holding a crystal ball — a symbol of the future she was denied. She turns away, knowing the child she should be holding is gone. In another image, a woman stands on a bridge between her dark past and a distant light-filled future. Yet shackles bind her in place — the chains of trauma, shame, and memory that ensure she can never fully cross.

In Swan Song, a girl dreams of dancing — of becoming a ballerina — but the image twists with mythic violence. Is she the dancer, or Leda in the clutches of the swan? Her dreams dissolve into survival, her innocence transformed into endurance. This painting, like the series as a whole, is a tribute to Ireland’s persecuted women — bound, stripped of dignity, yet somehow enduring.

These women, enslaved in the Magdalene laundries, toiled mercilessly in service of the Church and society. By scrubbing the linen of prisons, hospitals, and wealthy homes, they were told they were cleansing their souls. But in truth, their suffering was a stain on the conscience of a nation.

The Architecture of Containment stands as both elegy and exorcism — a testament to the warrior spirit within those women who survived, and a warning to ensure their story is never buried again. The truth is finally being unearthed — physically and figuratively. How we acknowledge and reckon with it now will become the architecture of our own history.

The work is ongoing.